An article from the Washington

County News, Abingdon, Virginia - Thursday, July 22, 1965

The small mountain

town of Abingdon, Virginia, shares a strange bond with the smaller

mountain town of West Jefferson, North Carolina. That bond is a railroad

that doesn't make any money, a railroad that runs through a beautiful

and ageless land, a railroad that carries no passengers, no mail,

and very little freight.

Yet it is a railroad

loved by everyone who knows it, and to a fortunate few it offers an

ever-changing spectacle of scenery.

But something

that doesn't pay cannot exist forever. And when this train ceases

to run Abingdon and the world of railroading will have lost something

it cannot replace.

In the early

1890s it was the Abingdon Coal and Iron Company Railroad and that

was its beginning. Then, in 1900, it became the Virginia-Carolina

Railroad and its tracks ran 16 miles into Damascus. It slowly grew

into the mountains, following the booming lumber industry, and in

1918 it became a part of the Norfolk and Western system, and its

name was changed to the Abingdon Branch, although people still called

it the Virginia Creeper. Seven trains a day wound into the hills.

People depended upon the railroad for mail, for news, for goods, for

transportation.

But the depression

came and lumber industry faltered. Freight business dropped. The automobile

became the method of transportation.

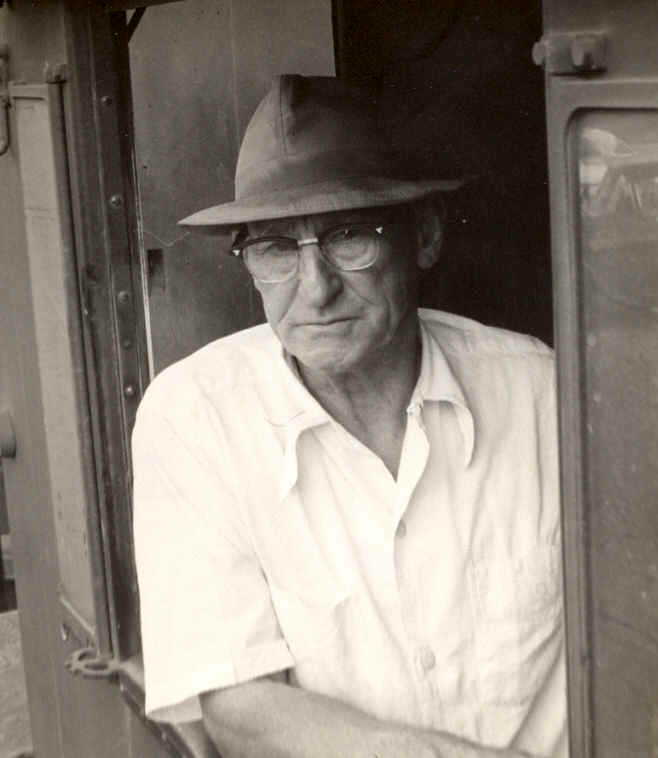

Engineer

Hughes

|

Then new kinds

of passengers came aboard the train, people not interested in going

to a particular place, but people wanting to see an unspoiled countryside.

And the train carried tourists into the waiting mountains, carried

them by cascading waterways, across 101 high wooden trestles, and

hoisted them up to the highest point on rails in Easter North America,

3, 557 feet into the sky. The steam billowed from the engine as it

huffed its way toward White Top Mountain.

In 1957 the huffing

and puffing of the steam engine was replaced with the whine and roar

of a diesel. One train a day ran now. Trucks took over carrying the

mail and freight over new highways into the hills. Soon the train

ran only three times a week, tourists were carried only on special

excursions. It became necessary to get special permission to ride

the train.

So we wrote to

Norfolk and Western in Roanoke and asked if we could take a trip on

the Virginia Creeper. Ben Dulaney, manager of news and community services,

wrote back and told us our trip had been approved, and that he was

coming down to see his mother in Glade Springs and was going to go

along with us. My cousin Preston Wolfe and I met Dulaney and Paul

Kabiness, the assistant road foreman, in Abingdon on a cloudy-bright

July morning, and when the train came along we all climbed aboard.

Crossing

Holston Lake.

Click on the photo for a comparison between 1965 and 2002.

|

We left Abingdon

and wound through the Knobs and soon came to the middle fork of the

Holston, then crossed the lake and rolled toward Damascus. The crew

of the train, engineer Hughes, brakemen Davis and Akers, and conductor

Rodenberry, went about their work with an an enjoyment few working

men have. They liked what they were doing, and took pride in their

job. When we left Damascus and started into the mountains I saw one

of the reasons.

There is a world

of shadow and light, of flickering water and enfolding mountains,

that few people have the chance to see. Most of us are restricted

to highways, with billboards blocking the landscape and other drivers

lunging at us from all directions, or we take occasional walks into

areas where the magnificence of the scenery is rivaled by the abundance

of discarded beer cans.

Damascus

station

|

This train follows

its twin ribbons of steel into a land inaccessible by road, where

man has not yet brought his questionable improvements. Around a bend

a startled deer will bound into the woods, and high in a tree a blacksnake

will stretch lazily in the summer heat. You can watch the movement

of wind along the side of a hill, the foaming water of a stream as

it falls down the mountain. Cattle will be grazing in the near fields,

and in the tiny villages along the way there are always children waving.

There is a tranquility to this landscape, and the men who make this

journey seem to have absorbed something of what they constantly pass

through.

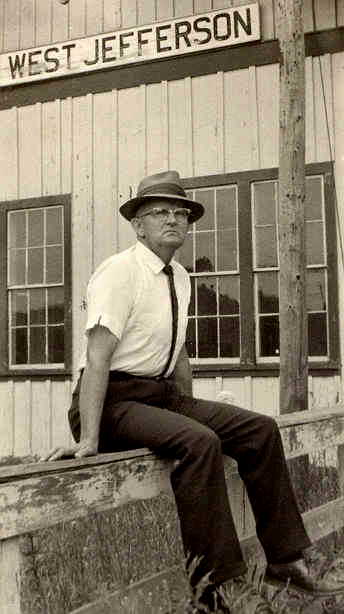

West Jefferson station

|

We moved our

way up through the mountains, circling and climbing and sometimes

looking back and seeing the track below us. Soon we were on the side

of White Top, going up a steep three-percent grade, and then we were

across the top and slanting down into North Carolina. There were more

roads to cross here, and the whistle shrieked to warn approaching

traffic. Eventually we came to West Jefferson. The train switched

a few cars and turned around, and we started back.

On the way back

I kept thinking of one thing. This train has been running for more

than 60 years, but the reasons for its existence are becoming fewer.

In another 60 years the Eastern Seaboard will be one great city, and

people will be crowded into smaller and smaller spaces. These people

will be wanting a place to go to be alone, they will be seeking a

private land where they can escape the crush of their cities.

And I wondered

where, in 60 years, this train will be.

Richard

Smith, July 1965

Link

to more photos from 1965

Virginia

Creeper Trail website